Hidden abstractions in the Diamond Kata

The other day my colleagues and I were doing the “Diamond Kata”. If you haven’t heard about code katas yet: it’s a coding exercise you’re supposed to do repeatedly in order to hone your skills. Each time, you might want to try different approaches, different programming languages or coding disciplines. I found the Diamond Kata interesting in its own right, let me tell you why.

The task

The Diamond Kata is giving you a seemingly simple task: write code that outputs text in a diamond shape. The edges consist of letters, starting with “A”. The last letter is given as an argument and also determines the size of the diamond. The diamond for A⇒B looks like this:

A

B B

A

The diamond for A⇒D would look like this:

A

B B

C C

D D

C C

B B

A

Looks pretty simple, right?

A solution

I’m going to present a solution in ruby. Let’s write some end-to-end tests first:

class TestDiamond < Minitest::Test

def test_end_to_end

assert_equal <<-EOS, Diamond.new("A").to_s

A

EOS

assert_equal <<-EOS, Diamond.new("B").to_s

A

B B

A

EOS

assert_equal <<-EOS, Diamond.new("C").to_s

A

B B

C C

B B

A

EOS

end

end

That was easy. So how are we going to solve this? Let’s start top down. We need to create the Diamond class and Diamond#to_s first. The string returned will be a concatenation of all the lines.

Diamond = Struct.new(:last) do

def to_s

lines.join

end

private

def lines

[] # ???

end

end

There’s only ever to be the same letter on every line and lines with the same letter look exactly alike. So we just need to figure out the right sequence of letters and have a method for creating the corresponding line. Let’s work on getting the sequence of letters right.

class TestDiamond < Minitest::Test

# [...]

def test_letters

assert_equal "A".chars, Diamond.new("A").letters

assert_equal "ABA".chars, Diamond.new("B").letters

assert_equal "ABCBA".chars, Diamond.new("C").letters

end

end

Diamond = Struct.new(:last) do

# [...]

def lines

letters.map(&method(:line_for))

end

def letters

(FIRST...last).to_a + (FIRST..last).to_a.reverse

end

def line_for(letter)

"" # ???

end

end

Well, this will do the job. Now on to implementing #line_for which will construct the string for one line. The tip and the bottom of the diamond are special as they only print one letter. For everything else, there will be some outer padding, repeated left and right, and some inner padding. We will need to do some ugly arithmetic with letters.

class TestDiamond < Minitest::Test

# [...]

def test_line_for

assert_equal "A\n", Diamond.new("A").line_for("A")

assert_equal " A \n", Diamond.new("B").line_for("A")

assert_equal "B B\n", Diamond.new("B").line_for("B")

assert_equal " B B \n", Diamond.new("C").line_for("B")

assert_equal "C C\n", Diamond.new("C").line_for("C")

end

end

Diamond = Struct.new(:last) do

# [...]

def line_for(letter)

outer_padding = " " * (width - (letter.ord - FIRST.ord))

if letter == FIRST

outer_padding + letter + outer_padding

else

inner_padding = " " * ((letter.ord - FIRST.ord) * 2 - 1)

outer_padding + letter + inner_padding + letter + outer_padding

end + "\n"

end

private

def width

last.ord - FIRST.ord

end

end

This took a few tries to get right, but seems to work. The end-to-end tests are passing now, we’re done. I wasn’t happy with this solution, though. Why? I was checking my code against Kent Beck’s four rules of simple design. Let me repeat them here:

Simple code

- passes test, i.e. works

- communicates intent

- contains no duplication

- uses a minimum amount of classes and methods

My problem was with rule 2., that the code doesn’t reflect the nature of the problem. You would never figure what the code does without running it or looking at the tests. It took me a few days to figure out another way.

The hidden abstraction

The task of the kata is not to output a certain random string. The diamond is a geometrical shape, it’s symmetrical. In math, you would draw something like this in a two dimensional coordinate system. So if we had some kind of canvas that we can render down to a string we could express the problem in a much nicer way. Let’s try this out! Here’s a really simple (square) text canvas:

class TestCanvas < Minitest::Test

def test_draw

canvas = Canvas.new(3)

canvas[0, 0] = "X"

canvas[1, 1] = "Y"

canvas[0, 2] = "Z"

canvas[2, 0] = "A"

assert_equal <<-EOS, canvas.to_s

X A

Y

Z

EOS

end

end

Canvas = Struct.new(:size) do

def to_s

rows.map { |row| row + "\n" }.join

end

def []=(x, y, value)

rows.fetch(y)[x] = value

end

private

def rows

@rows ||= Array.new(size) { " " * size }

end

end

On this canvas we need to paint every letter four times. We don’t need a special case for the tips any more: the tips will get painted more than once, at the same position. I introduce the radius of the diamond. We need to shift everything by this value in X and Y direction as our origin 0, 0 is in the top left corner. Here’s something that works:

Diamond = Struct.new(:last) do

FIRST = "A"

def to_s

draw!

canvas.to_s

end

private

def draw!

FIRST.upto(last).zip(

0.upto(radius),

radius.downto(0)

).each do |letter, x, y|

canvas[ x + radius, y + radius] = letter

canvas[-x + radius, y + radius] = letter

canvas[ x + radius, -y + radius] = letter

canvas[-x + radius, -y + radius] = letter

end

end

def canvas

@canvas ||= Canvas.new(width)

end

def radius

@radius ||= last.ord - FIRST.ord

end

def width

radius * 2 + 1

end

end

I already like this solution much better.

- We got rid of the special case.

- The symmetry of the diamond shape is reflected by the drawing operations.

- The

Canvasclass can be tested independently and is a component that we can easily reuse.

There’s also a thing I didn’t mention previously: we had to make Diamond#letters and Diamond#line_for public so that they could be tested. But they are really an implementation detail that no other code should depend upon. With the current implementation I’m quite happy with the feedback that the end-to-end test provides. Maybe some minor thing: the #draw! method still has some duplication, the drawing of letter looks repetitive as we always need to add the radius. According to the Four Rules of Simple Design, this is something to look out for. So let’s see if we can improve.

More abstractions

Operations in 2D space are a well known subject. Moving around by a fixed amount is called translation. Let’s implement this as a decorator:

class TestCanvas < Minitest::Test

def test_translation

canvas = Translation.new(Canvas.new(3), 1, 1)

canvas[0, 0] = "A"

assert_equal <<-EOS, canvas.to_s

A

EOS

end

end

class Translation < SimpleDelegator

def initialize(canvas, offset_x, offset_y)

super(canvas)

@offset_x = offset_x

@offset_y = offset_y

end

def []=(x, y, value)

__getobj__[x + offset_x, y + offset_y] = value

end

private

attr_reader :offset_x, :offset_y

end

The decorator logic calls for a bit of boilerplate, but the end result is nice and simple. Let’s see how we can put this to good use. Two methods in Diamond will need to change, Diamond#draw! and Diamond#canvas.

Diamond = Struct.new(:last) do

# [...]

private

def draw!

FIRST.upto(last).zip(

0.upto(radius),

radius.downto(0)

).each do |letter, x, y|

canvas[ x, y] = letter

canvas[-x, y] = letter

canvas[ x, -y] = letter

canvas[-x, -y] = letter

end

end

def canvas

@canvas ||=

Translation.new(

Canvas.new(width),

radius, radius

)

end

So each drawing operation got simpler at the expense of a more complicated canvas setup. We still have four drawing operations going on, though. The obvious solution is to use a loop instead like this

Diamond = Struct.new(:last) do

# [...]

def draw!

FIRST.upto(last).zip(

0.upto(radius),

radius.downto(0)

).each do |letter, x, y|

[[x, y], [-x, y], [x, -y], [-x, -y]].each do |coords|

canvas[*coords] = letter

end

end

end

This removes duplication but makes the #draw! method harder to read. Maybe we can solve this in a similar fashion? Let’s look at it from another angle: we’re drawing a symmetrical shape, this means that we are mirroring over the X and Y axes. So the thing we need is a reflection. This should be pretty simple to do.

class TestReflection < Minitest::Test

def test_reflection

canvas =

Reflection.new(

Translation.new(

Canvas.new(3),

1, 1

),

-1, 1

)

canvas[0, 0] = "A"

canvas[1, 1] = "B"

assert_equal <<-EOS, canvas.to_s

A

B B

EOS

end

end

class Reflection < SimpleDelegator

def initialize(canvas, factor_x, factor_y)

super(canvas)

@factor_x = factor_x

@factor_y = factor_y

end

def []=(x, y, value)

__getobj__[x, y] = value

__getobj__[x * factor_x, y * factor_y] = value

end

private

attr_reader :factor_x, :factor_y

end

This looks very similar to Translation, using multiplication instead of addition. The difference is that we’re still drawing in the original location. In order to be even more general, you could introduce a stack of canvases that get layered on top of each other during rendering. I chose not to go this route here. So what does this mean for our Diamond class?

Diamond = Struct.new(:last) do

# [...]

def draw!

FIRST.upto(last).zip(

0.upto(radius),

radius.downto(0)

).each do |letter, x, y|

canvas[x, y] = letter

end

end

def canvas

@canvas ||=

Reflection.new(

Reflection.new(

Translation.new(

Canvas.new(width),

radius, radius

),

1, -1

),

-1, 1

)

end

The setup of our canvas looks pretty complex now. Is this still simple design? Duplication is reduced, but we have more classes working together. Whether this is all worth it depends on the context. For me this is just an exercise, so I can do what I please. But what if this was happening in a business context? If the business is trying to create a terminal-based text-only drawing program for UNIX-nerds, there’s a high likelyhood that our investment in composable classes will pay off quickly. If on the other hand this task was only a one-off job to help in creating a new company logo, our efforts would have been wasteful and our first version would have been good enough.

A parable for hidden abstractions

In hindsight the value of introducing the Canvas abstraction is obvious. Why didn’t I see it earlier? I think this is due to my upbringing as a programmer. A programmer learns how to do useful stuff with a dumb machine. We’re aware of the limits of our programming environments and take pride in how we’re still getting useful stuff done. So it’s only logical that start to think like the machine, we break the output up into individual lines and start to solve the smaller problem of creating a single line. The problem is that this is disregarding the outside context and therefore obscures the nature of the task.

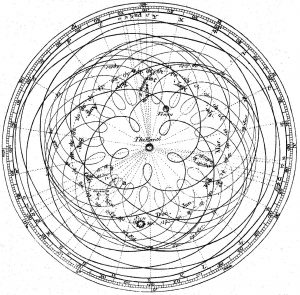

This reminded me of the history of astronomy. In antiquity, astronomers were able to calculate the motion of the planets pretty accurately even though they were using the geocentric model. The Ptolemaic system was pretty complex, it assumed that planets were moving in epicycles along deferents. Similar to our first implementation, it worked just fine. But as we know today, it’s more useful to put the sun in the center. Contemporary programmers struggle with finding a better point of view just as much as the astronomers of yore.

Abstractions and TDD

People have been saying that TDD leads to better design and I tend to agree. But TDD doesn’t write code, it doesn’t create abstractions and it doesn’t always make it obvious what next step to take. A nicely factored implementation is easy to test – it’s our job as programmers to conceive it.

References

- Source code on github

- Original description of the diamond kata on Seb Rose’s blog

- A solution in Scala using TDD with property-based tests by Nat Pryce

- Jon Jagger found another interesting solution

- Ptolemaic system on Wikipedia